I discovered my calling early on in my career working at the archaeological site of Cacaxtla in Mexico: I learned to listen, to deeply understand what was in front of me, and then to weave the different threads into a tapestry that reflected the dialogue.

In 2013, Michael Govan, CEO and Director at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), recruited me to come to Los Angeles to help him with a bold, transformative project for the museum: to construct a new building for the permanent collections that would serve as a radically new vessel of knowledge: an Encyclopedic Museum where cultures from around the world, past and present, will be shown in dialogue and without hierarchies. I firmly believed in this vision and accepted the challenge to leave my country as I had finished my tenure as the Director of the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City.

I have developed an innovative and knowledgeable leadership style based on a long and versatile career in which I have been a constructive and highly motivated professional, never afraid to take on new challenges.

In 1988, the last and fifth year of my training as an art conservator in Mexico City, I was awarded a scholarship to specialize in scientific analysis of works of art at the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, Switzerland, where I stayed for one year. When I came back to Mexico to finish my studies, I was chosen by the Director of the National School of Conservation to be the conservator in charge of the Red Temple, a newly discovered pre-Columbian mural painting in the archaeological site of Cacaxtla. Using my new scientific skills, I embarked on research through which I discovered the specific materials and methods used to create these ancient, beautiful murals. I earned my degree in Conservation and was awarded a prize for my dissertation, which entailed its publication. In my book Methodology for the Study of Pre-Hispanic Mural Painting Techniques (1990), I described the technical solutions and achievements that these ancient Mesoamerican artists accomplished, emphasizing the connections between their knowledge of the natural world (what we call science today), their worldview, and their aesthetic pursuits.

Given my innovative research methodology and original findings at Cacaxtla, I was recruited by the University of Mexico to become a full researcher and leader of conservation and art history at a young age. I was invited to work closely for almost two decades with an interdisciplinary team of scholars devoted to studying the numerous archaeological sites with mural paintings in Ancient Mexico. This experience has honed my ability to collaborate with diverse teams, a crucial skill in the cultural sector. The Mexican Pre-Hispanic Mural Painting Project published all of my research throughout the years.

To undertake the scientific analysis of all of these Mesoamerican mural paintings, I traveled to diverse international laboratories in both the US and Europe. I was helped by the generous support of scientists in these institutions, without whom I would not have been able to accomplish my work. These publications, in turn, inspired many other researchers in Mexico and around the world, and a new field of study bridging Conservation and Art History consolidated.

My unique combination of scientific and art historical knowledge granted me the opportunity to study for my PhD in art history at Yale University. At Yale, I decided to embark on a new area of study: Indigenous early Colonial Mexico. I specialized in what I considered one of the most outstanding works produced in the Americas: a bilingual (Nahuatl and Spanish), fully illustrated, 12-volume encyclopedia about the life and culture of Ancient and Colonial Mexico known as the Florentine Codex (1575-1577). I was the first art historian to study the creation process and methods used to create the Florentine Codex. I identified the hands of artists; I investigated their training and knowledge, establishing that these painters and writers were fluent in both the Ancient Mexican and the European Renaissance painting, drawing, and engraving traditions. I wrote my PhD dissertation on the images of the last and twelfth book of the encyclopedia, devoted to the History of the Conquest of Mexico from the point of view of the indigenous peoples. I proposed that their paintings of the conquest were, in fact, “visual texts” that had an ulterior meaning, just as the painted images in the pre-Conquest manuscripts had.

At the time I was writing (2000-2004), these vignettes were considered of lesser interest than the Nahuatl and Spanish texts of the conquest because of their “Europeanized painting style.” My research, instead, advanced the notion that these images were the new indigenous international style. The Indigenous authors were cognoscente and conscious that they were living in another era. They were active participants in creating the modern, global, interconnected world that was born with the inclusion of the Americas during the Renaissance.

My dissertation allowed me to apply for permission to study the original 12-volume encyclopedia in the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana. In 2006, I traveled with my two young daughters (4 and 7 at the time) to Florence, where they attended school and became two little Italian kids for a while. Together with a group of scientists from the University of Florence, we identified the natural-based organic pigments and the minerals used in the images.

In the book Colors of the New World (Getty Research Institute, 2016), I showed how the colors gave an unseen meaning to the images. Pigments were used to encode the nature of what was represented. The moon had a humid, feminine, telluric nature and thus was painted with minerals obtained from the entrails of the earth. Portrays of rituals and warriors devoted to the solar calendar were colored with lake pigments made with substances that grow with sunlight, like flowers, bark trees, and insects. I also advanced the theory that these images, through their colors, were conceived not as mere representations but as impersonators of life energies. I called attention to the historical context in which all of these materials were created: the pandemic of 1576 when 90% of the indigenous population of Central Mexico perished. The Florentine Codex is, in my view, a work made so that a civilization would survive into the future. As I listened to their dialogue, I was their voice through my writing; I needed to become the storyteller of their quest in the present.

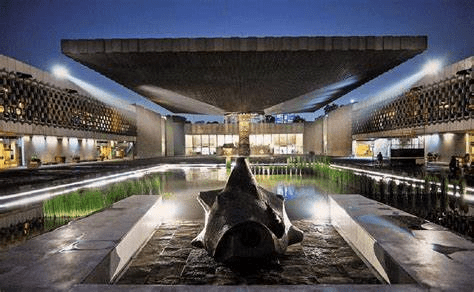

I was appointed the Director of the National Museum of Anthropology (Museo Nacional de Antropología) in Mexico City in 2009 and stayed in this position until 2013. I had been a scholar and professor at the University of Mexico and taken care of the finances and grant writing for research projects and publications, but I found myself suddenly responsible for the most vast and valuable Ancient American collections in my country, for hundreds of employees, and a large yearly budget. In the Museo de Antropología, I understood that the mission I had chosen of listening to the indigenous historical voices and perspectives had just taken a new, more committed turn. The museum world opened a new door for me as a platform for impact and communication.

The fantastic power of museums is that they can become vessels that contain and give knowledge; they can be guardians and creators reflecting a multiplicity of perspectives. Museums are stewards of works that share the awe of existence and display our inner longings, hopes, loves, and fears in many culturally different ways. I dedicated myself to managing the institution wisely by getting funds to restore the facilities and bringing stability through acknowledgment and recognition of the workers’ skills and needs and to trying to bridge the well-respected pre-Hispanic Indigenous collections with the present-day Indigenous communities. I championed many innovative projects, especially in the care of the collection, systematizing the data, and fostering new research. I managed 18 international exhibitions, and because of this intense international work, I met Michael Govan, who opened the possibility of amplifying my work to the whole American continent.

I became Deputy Director of LACMA in 2013. I established an innovative curatorial program that creates exhibitions and mentors new curators. The program’s relevance is reflected by the commitment of its supporters, garnering the attention and funding from the Mellon, Annenberg @ GRoW, and Greenberg Foundations. The Art of the Ancient Americas program mentors through active best practices: intelligent and committed diplomacy with the countries of origins; creative and sustained relations with Indigenous communities in these countries; constant work with contemporary artists to bridge the gap between the past and the present, and to make the ancestral collections relevant and inspiring for our visitors. Guided by this vision, I have curated four major traveling exhibitions and have mentored and supervised the making of seven smaller projects. I have also continued my study of the Florentine Codex, acting as Co-Head of the Digital Florentine Codex Project—an enhanced online edition of the manuscript, complete with Nahuatl and Spanish transcriptions, English and Spanish translations, and searchable texts and images—developed at the Getty Research Institute between 2010 and 2024.

As Director of LACMA’s Conservation department, I supervised and led the construction of a new Conservation Center within LACMA’s Pavilion of Japanese Art, adapting existing spaces for four new specialized conservation studios: Paintings, Objects, Paper, and Textiles, as well as a Science Laboratory and a new Technical Imaging and Photography studio. We moved into this new facility in March 2020. I devised and championed new programs to help diversify Conservation, one of the least diverse fields in the Museum world. I helped create a pilot project in collaboration with Fisk University, one of the HBCU colleges, in which students can learn skills to become registrars with a firm base in preventive conservation concepts that will allow them to become practitioners in smaller museum galleries that often lack the possibility of hiring these professionals. Additionally, helped start a research project with the Getty Conservation Institute to promote more equitable, accessible, and climate-responsible practices. We have been measuring the impact of more relaxed environmental conditions, such as light, humidity, and temperature, on our collections when we send our works to galleries and museums so that we will be able to establish the Bizot standards in our new Geffen Galleries.

I have a unique ability to communicate complex ideas to a wider audience, making me an effective storyteller and educator. This ability has led to a rich and impactful career in art history, conservation, and museum leadership.